Clinical Clarity or Cinematic Softness?

In the last years one of the most intense discussions online is whether to produce sharp clinical footage or soft footage on video productions, brands offering sharper clinical lenses with more pegapixels and other brands offering a more stylistic soft image with “character”, and as usual, influencers and so-called experts tell their audience what they should use instead of just showing what the gear can do.

How do we get here? Well, here is the issue: Photographers like sharp images, they are natural pixel peepers, while cinematographers usually like clean, soft moving pictures that enhance actors’ faces and hide their imperfections. That is why, from the beginning, cinematographers used everything from baseline filters to nylon stockings over the lenses to soften the image, and while this was happening, landscape photographers like Ansel Adams were creating the “Group f/64” – yes, the name of the group implies having everything in focus and as sharp as possible.

Group f/64 was a groundbreaking collective of photographers formed in the San Francisco Bay Area in the early 1930s. It represented a pivotal shift in American photography, championing “straight photography”, sharp, precise, unmanipulated images that celebrated the camera’s unique ability to record the world with clarity and detail, over the softer, more painterly style of Pictorialism that had dominated art photography for decades.

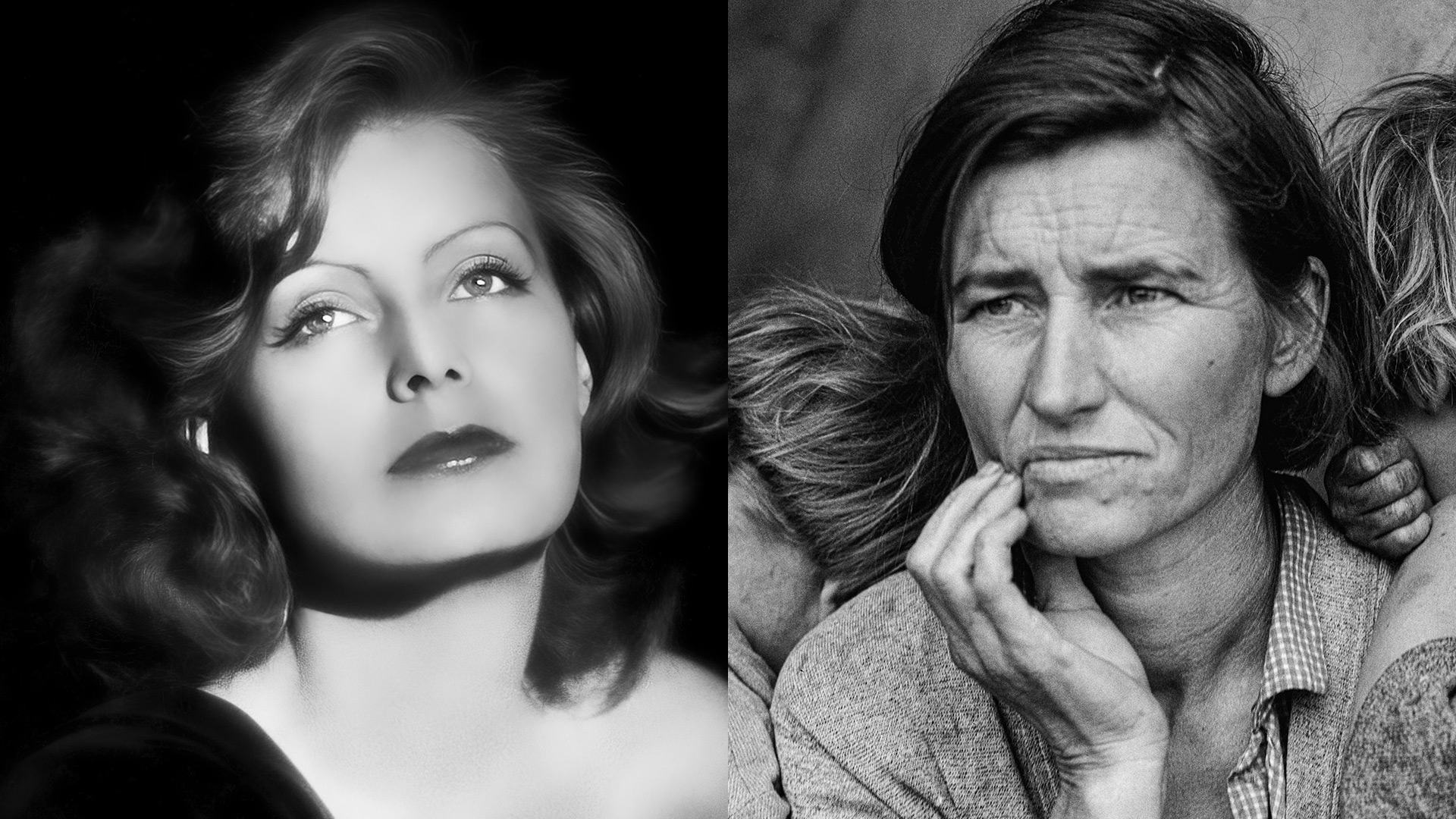

During Hollywood’s Golden Age (roughly 1920s-1950s), diffusion was used extensively on lenses to create the iconic glamorous, soft-focus look that flattered stars, especially leading actresses. Techniques like stretching fine nylon stockings (often black Christian Dior #10 denier or similar sheer nets) over the lens, usually mounted behind it to avoid visible patterns, softened skin details, reduced harsh sharpness, smoothed wrinkles and imperfections, and produced a gentle glow or halation around highlights for a dreamy, ethereal quality. This was essential for the era’s studio lighting setups (with arc lights and high-contrast blacks), film stocks, and lenses, which could otherwise appear too clinical or reveal flaws under the intense scrutiny of close-ups. It helped maintain the “star-making” illusion of flawless beauty and romance, as seen in portraits of icons like Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, or Marilyn Monroe, and became a hallmark of classic Hollywood glamour photography and cinematography long before modern glass diffusion filters existed.

Recently, with the DSLR revolution, photographers and camera reviewers were able to transition to “filmmakers,” bringing with them the old habits of sharp photography into “cinema”. But cinema hasn’t typically been sharp at all, look at any of Christopher Nolan’s movies, Oppenheimer for instance, and you’ll see many soft images. That is why we cannot take every piece of advice from non-filmmakers as gospel, or even from successful filmmakers, there are just opinions. You are the one who decides if you want a clear, clinical image or a soft one, it depends on what you want to express with your footage or photos.